Today is the third anniversary of the first day of the 2-day November 2009, FDA public hearing on the Promotion of Food and Drug Administration-Regulated Medical Products Using the Internet and Social Media Tools (see here, here, and here).

Shortly after that hearing, some FDA staffers lead us to believe that FDA would come out with social media regulatory guidance for the pharma industry by the end of 2010 (see here). That never happened.

Instead, FDA kept procrastinating and throwing roadblocks in the way such as proposing further studies (see, for example, "FDA's Proposed Web Study Will Further Delay Social Media Guidelines").

Meanwhile, to add insult to injury, Tom Abrams, head of FDA's DDMAC (now OPDP), keeps showing up at industry meetings where industry leaders were expecting him to announce progress towards issuing draft guidance. At one such meeting in February, 2011, Abrams spent a scant 4 minutes discussing social media guidance (read this). At that meeting, he said FDA would NOT "do guidance on specific technology platforms such as YouTube, Facebook, or Twitter. Those things are really big now, but you know what, two years from now who knows what the next thing [will be]?" Well, guess what? It's almost two years later and YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter are still BIG, if not BIGGER and nothing has come along that's bigger. [BTW, Abrams also pooh-poohed Groupon, which now seems prophetic! And Google eliminated sidewiki, which was a big concern at the 2009 public hearing (read this).]

In recognition of the role Abrams has played in all this procrastination regarding social media guidance from FDA, I hereby present to Abrams the first ever Pharmaguy Social Media Procrastination AwardTM.

This award, as you may notice, is the antithesis to the famous Pharmaguy Social Media Pioneer Award, which was recently given to the sanofi US diabetes team (see here).

The iconic Hawaiian shirt in the "Procrastinator Award" is dark, symbolizing the negative implications of procrastination versus the bright yellow, positive Hawaiian shirt image used in the "Pioneer Award."

Abrams continues to show up at industry meetings promising that social media guidance is a high priority at FDA and it will be coming soon -- perhaps as "soon" as July, 2014 (see here). Yet, we've heard it all before. That's why I think it is fitting that Abrams receive the the "Procrastinator Award."

If Abrams lives up to his latest promise -- which is doubtful, IMHO -- it would have taken the FDA only 4 years and 8 months to issue draft social media guidance. In terms of Internet/social media timeframes -- in which 2 years can bring BIG changes -- this is procrastination on an epic scale. But in terms of FDA guidance timeframes, 4 years and 8 months is par for the course (see, for example, "A Cautionary Tale for Anyone Expecting FDA Social Media Guidelines Any Time Soon").

Showing posts with label FDA. Show all posts

Showing posts with label FDA. Show all posts

Monday, November 12, 2012

Thursday, November 8, 2012

Will FDASIA Get FDA Off Its Butt to Finally Issue Social Media Guidance?

I noted with interest the headline in today's FDA News email: "OPDP: Social Media Guidance Will Be High Priority in 2013"." Here's the teaser copy that explains what's going one:

"The Office of Prescription Drug Promotion (OPDP) has placed developing social media guidance at the top of its work plan for 2013, director Thomas Abrams says. Abrams outlined the offices priorities at the Pharmaceutical Regulatory and Compliance Congress in Washington, D.C. The social media guidance is of critical importance because the Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act (FDASIA) mandates the agency produce the guidance by July 9, 2014."I have three comments regarding this:

- I reported back in July 2012 (here), about a little-noticed "Miscellaneous Provision" of the "Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act", which was signed into law by president Obama on July 10, 2012. This provision simply states: "Not later than 2 years after the date of enactment of this Act, the Secretary of Health and Human Services shall issue guidance that describes Food and Drug Administration policy regarding the promotion, using the Internet (including social media), of medical products that are regulated by such Administration."

- This is NOT the FIRST time Abrams has promised that social media guidance was a "priority." At the November, 2009, FDA public hearings on social media, Abrams said he heard "loud and clear from folks in this room" (ie, pharma companies) that "we want guidance on social media... We heard that message. Let me tell you that we are devoting a lot of resources and effort to this" (read this: "Is It Time for Abrams to Leave?").

- Although it's nice that Abrams says social media guidance will be "at the top" of FDA's work plan for 2013, I wonder why it was REMOVED from the published work calendar as far back as 2011 (read this: "FDA Drops Social Media from Its 2011 Guidance Agenda").

So, will Abrams keep his promise this time? Pardon me for being a doubting Thomas. You think a "do nothing" Congress that's facing a "fiscal cliff" will spend any energy to make sure the above "provision" is adhered to by the FDA? I said it before and I'll say it again now: If FDA misses the deadline set by FDASIA, what can Congress do? Write a letter? Not another letter from Charles Grassley! I'm sure FDA is shaking in its boots.

Tuesday, November 6, 2012

Pharma Testimonial Videos Overstate Efficacy More Often Than Other Ads

Mark Senak over at Eye On FDA Blog has analyzed 235 Warning Letters (WLs) and Notice of Violation (NOVs) letters issued by FDA's Office of Pharmaceutical Drug Promotion (OPDP) since 2005. He cataloged 600 violations, including:

When Senak specifically looked at letters regarding pharma marketing videos (excluding TV DTC ad videos), he found that 80% of the violations concerned risk minimization (40%) or overstatement of efficacy (40%). Below is the remake of his pie chart of these data (for the original data see "Viewing Video’s Regulatory Profile").

What's interesting is that these videos -- mostly patient and physician testimonials -- overstate efficacy at TWICE the average for all kinds of promotions (40% for videos vs. 21% for all ads, including video). Senak postulates that "when people talk about their own experiences with a treatment, [they] may include reference to outcomes that is not typical or supported by clinical data."

An example of a video that overstated efficacy was a video testimonial featuring Ty Pennington posted on youtube.com by Shire. FDA said "Both the webpage and video overstate the efficacy of Adderall XR; the video also omits important information regarding the risks associated with Adderall XR use."

The problem with FDA letters is they usually are sent well after the cow has walked through the open barn door! See, for example, "Vyvanse Warning Letter: Too Late! Shire Got Rid of Ty Pennington Long Ago!"

- risk omission or minimization,

- superiority claims,

- overstatement of efficacy,

- unsubstantiated claims and

- broadening of indication

When Senak specifically looked at letters regarding pharma marketing videos (excluding TV DTC ad videos), he found that 80% of the violations concerned risk minimization (40%) or overstatement of efficacy (40%). Below is the remake of his pie chart of these data (for the original data see "Viewing Video’s Regulatory Profile").

What's interesting is that these videos -- mostly patient and physician testimonials -- overstate efficacy at TWICE the average for all kinds of promotions (40% for videos vs. 21% for all ads, including video). Senak postulates that "when people talk about their own experiences with a treatment, [they] may include reference to outcomes that is not typical or supported by clinical data."

An example of a video that overstated efficacy was a video testimonial featuring Ty Pennington posted on youtube.com by Shire. FDA said "Both the webpage and video overstate the efficacy of Adderall XR; the video also omits important information regarding the risks associated with Adderall XR use."

The problem with FDA letters is they usually are sent well after the cow has walked through the open barn door! See, for example, "Vyvanse Warning Letter: Too Late! Shire Got Rid of Ty Pennington Long Ago!"

Labels:

ADHD,

FDA,

Legal/Regulatory,

Shire,

Testimonials,

Vyvanse,

warning letters,

YouTube

Thursday, November 1, 2012

FDA's "Mobile Medical Apps" Scope of Oversight Pyramid: Confusion Abounds

"Consider the 'Mobile medical apps Proposed Scope for Oversight' issued by CDRH [FDA's Center for Devices and Radiological Health]," said DrugWonk Peter Pitts (here). "It’s a pyramid divided into three parts":

Pitts describes these parts of the pyramid:

I notice that many reporters and drug industry people refer to "mobile medical apps" when describing apps that are CLEARLY at the bottom of CDRH's pyramid. An example is the article titled "11 Super Mobile Medical Apps" that offers these examples of apps, which clearly should NOT be called MMAs:

Pitts describes these parts of the pyramid:

- The top of the pyramid includes mobile medical apps that are traditional medical devices or a part or an extension of a traditional medical device. Clearly within the scope of being regulated as medical devices.

- The middle section includes patient self- management apps and simple tracking or trending apps not intended for treating/adjusting medication. This is the area, as defined by CDRH, for enforcement discretion

- The bottom section are devices that are not deemed “mobile medical apps” and, as such, have no regulatory requirements.

So, FDA has reserved the term "Mobile Medical App" (MMA) to mean a medical app that meets its medical "device" definition. From now on I will have to be careful NOT to use that term/phrase when talking about mobile apps that clearly are NOT medical devices. I guess we should use "Mobile Health Apps" instead.

I notice that many reporters and drug industry people refer to "mobile medical apps" when describing apps that are CLEARLY at the bottom of CDRH's pyramid. An example is the article titled "11 Super Mobile Medical Apps" that offers these examples of apps, which clearly should NOT be called MMAs:

"Among the innovative mobile medical apps we found is one that lets doctors use interactive diagrams to show patients what's happening with their bodies, where procedures will be done, and exactly what will happen during different procedures. Alternatively, patients can use this app to get doctors to provide detailed visual answers to their questions."Unfortunately, FDA's co-optation of "mobile medical app" to refer to health apps requiring regulation as medical devices confuses the discussion, which up until now used the term to describe any health-related app that a physician or patient might use. This may be why PhRMA and other drug industry spokespeople are so fearful of FDA regulations hampering innovation within the "mobile health app" arena (see, for example, "FDA Mobile Regulatory Fear Mongering by PhRMA").

Monday, October 29, 2012

My POV Regarding Regulation of Pharma Mobile Medical Apps

The pharmaceutical industry has to police itself with regard to development of medical apps. There has to be good documentation of the testing of apps to ensure their correctness.

That's the summary of my point of view (POV) regarding the pharma HOTSPOT topic: "Should Pharma reconsider its mobile application approach with FDA guidance looming?" See the annotated video below:

A "counterpoint" was offered by Dr. Chetan Vijayvergia, PhD, Director of Medical Strategy, Ignite Health, on Ignite Health's Pharma HOTSPOT web site. Dr. Vijayvergia's point was "The apps that are currently being created in the Pharma space don’t have a predicate in the FDA database. Pharma needs to reconsider the mobile approach to actively help the FDA shape industry guidance" (see here).

Vijayvergia contends that the current FDA draft guidance for MMAs "casts a very wide net" and if pharma app developers are not careful, their apps can get "dinged as an MMA [mobile medical application]" and be subject to regulation as a medical device.

The fear that FDA is casting too "wide a net" over MMAs was first expressed by PhRMA (see "FDA Mobile Regulatory Fear Mongering by PhRMA"). IMHO, the FDA was pretty clear about staying away from most health-related apps aimed at consumers such as diet apps, etc.

The Best Defense Against Zealous FDA Regulation is Self-Regulation!

In addition to offering FDA its POV regarding what is and what is not a MMA subject to medical device regulation, the pharma industry, IMHO, should begin policing itself to develop MMAs that comply with standards such as Happtique's App Certification Program; listen to this podcast regarding that:

You may also enjoy reading these previous posts regarding pharma mobile medical apps:

That's the summary of my point of view (POV) regarding the pharma HOTSPOT topic: "Should Pharma reconsider its mobile application approach with FDA guidance looming?" See the annotated video below:

A "counterpoint" was offered by Dr. Chetan Vijayvergia, PhD, Director of Medical Strategy, Ignite Health, on Ignite Health's Pharma HOTSPOT web site. Dr. Vijayvergia's point was "The apps that are currently being created in the Pharma space don’t have a predicate in the FDA database. Pharma needs to reconsider the mobile approach to actively help the FDA shape industry guidance" (see here).

Vijayvergia contends that the current FDA draft guidance for MMAs "casts a very wide net" and if pharma app developers are not careful, their apps can get "dinged as an MMA [mobile medical application]" and be subject to regulation as a medical device.

The fear that FDA is casting too "wide a net" over MMAs was first expressed by PhRMA (see "FDA Mobile Regulatory Fear Mongering by PhRMA"). IMHO, the FDA was pretty clear about staying away from most health-related apps aimed at consumers such as diet apps, etc.

The Best Defense Against Zealous FDA Regulation is Self-Regulation!

In addition to offering FDA its POV regarding what is and what is not a MMA subject to medical device regulation, the pharma industry, IMHO, should begin policing itself to develop MMAs that comply with standards such as Happtique's App Certification Program; listen to this podcast regarding that:

Listen to internet radio with Pharmaguy on Blog Talk Radio

You may also enjoy reading these previous posts regarding pharma mobile medical apps:

Thursday, September 6, 2012

FDA Caught Speeding. Puts Public Safety at Risk.

"An FDA effort to speed approval of new medicines allowed drugs for stroke prevention, cancer and multiple sclerosis onto the market without proper safety analysis, according to two drug-safety experts," reports the Wall Street Journal in a review (here) of a "viewpoint" recently published in JAMA.

Peter Pitts of Drug Wonks says: "As usual, Janet Woodcock [Director of the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research at FDA] places the matter in the appropriate perspective. 'I'd like to stress that where there are unmet medical needs, the public has told us they are willing to accept greater risks,' Dr. Woodcock said. "The cancer community in particular says we haven't used accelerated approvals enough.'" Pitts adds this zinger:

"Here’s the truth -- there is no such thing as a 'safe' drug. It's the patient who must understand the risks required to achieve the benefit. That’s why the patient voice must be heard during all phases of the regulatory review process."

Unfortunately, I don't think Pitts actually read the piece in JAMA. The drug safety expert authors of that piece (Thomas J. Moore and Curt D. Furberg) did not claim that drugs approved by the FDA should be "safe." They made the argument that accelerated approval by FDA of several powerful drugs with UNKNOWN safety issues were no better at improving outcomes than drugs currently on the market whose safety issues are well-known.

"Although enabling new drugs with a favorable benefit-to-harm balance to become available to patients more rapidly is a laudable goal," said Moore and Furberg, "the underlying question is what public health risks are taken when drugs are approved for widespread use while important safety questions remain unanswered."

The authors cite several specific drugs that were fast-tracked for approval without adequate safety information available. I'd like to focus on one: Dabigatran for prevention of stroke. Dabigatran is marketed as Pradaxa by Boehringer Ingelheim (BI).

According to Moore and Furberg, Pradaxa benefited from "3 different FDA policies promoting innovation. This drug received both Fast Track and Priority Reviews and was studied in a single large phase 3 trial rather than in at least 2 pivotal trials, as normally required...Within less than a year of approval, 1 survey showed that dabigatran accounted for more serious adverse drug events reported to the FDA during the second quarter of 2011 than any other regularly monitored drug. Risk of hemorrhage was prominent in older patients (median age, 80 years), a subgroup for whom declining kidney function or other factors may have increased bleeding risk. Both a manufacturer package insert revision and the European Medicines Agency have called for closer monitoring of kidney function, a needed step because even moderate kidney impairment increases dabigatran levels more than 2-fold. In addition, unlike warfarin, no antidote is available for use in bleeding emergencies related to dabigatran. Evidence was beginning to emerge that dabigatran-related bleeding— whether from trauma or as an adverse effect—may be more difficult to treat than warfarin-related bleeding."

Couple this safety issue with the promotion of Pradaxa in the media as a "super pill" and a "revolutionary drug" (see "Bad Journalism or Bad Pharma?") and you end up with a real public safety issue that patients should be concerned about. BI itself stoked this Pradaxa-mania (read, for example, "BI Masters the Art of WOM through Its 'Parrots,' er, Spokespersons" and "Full BOEHR(inger) Social Media Reporting of RELY Trial Results").

Sadly, Woodcock may have heard from "patient advocates" paid by pharma companies to testify before the FDA, but who advocates for the patients harmed by drugs like Pradaxa? Their stories are locked in the FDA's adverse event database, which is not generally cited during drug approval Hearings at the FDA.

Not to mention the impact of DTC advertising on the public's willingness to accept greater risk:

Peter Pitts of Drug Wonks says: "As usual, Janet Woodcock [Director of the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research at FDA] places the matter in the appropriate perspective. 'I'd like to stress that where there are unmet medical needs, the public has told us they are willing to accept greater risks,' Dr. Woodcock said. "The cancer community in particular says we haven't used accelerated approvals enough.'" Pitts adds this zinger:

"Here’s the truth -- there is no such thing as a 'safe' drug. It's the patient who must understand the risks required to achieve the benefit. That’s why the patient voice must be heard during all phases of the regulatory review process."

Unfortunately, I don't think Pitts actually read the piece in JAMA. The drug safety expert authors of that piece (Thomas J. Moore and Curt D. Furberg) did not claim that drugs approved by the FDA should be "safe." They made the argument that accelerated approval by FDA of several powerful drugs with UNKNOWN safety issues were no better at improving outcomes than drugs currently on the market whose safety issues are well-known.

"Although enabling new drugs with a favorable benefit-to-harm balance to become available to patients more rapidly is a laudable goal," said Moore and Furberg, "the underlying question is what public health risks are taken when drugs are approved for widespread use while important safety questions remain unanswered."

The authors cite several specific drugs that were fast-tracked for approval without adequate safety information available. I'd like to focus on one: Dabigatran for prevention of stroke. Dabigatran is marketed as Pradaxa by Boehringer Ingelheim (BI).

According to Moore and Furberg, Pradaxa benefited from "3 different FDA policies promoting innovation. This drug received both Fast Track and Priority Reviews and was studied in a single large phase 3 trial rather than in at least 2 pivotal trials, as normally required...Within less than a year of approval, 1 survey showed that dabigatran accounted for more serious adverse drug events reported to the FDA during the second quarter of 2011 than any other regularly monitored drug. Risk of hemorrhage was prominent in older patients (median age, 80 years), a subgroup for whom declining kidney function or other factors may have increased bleeding risk. Both a manufacturer package insert revision and the European Medicines Agency have called for closer monitoring of kidney function, a needed step because even moderate kidney impairment increases dabigatran levels more than 2-fold. In addition, unlike warfarin, no antidote is available for use in bleeding emergencies related to dabigatran. Evidence was beginning to emerge that dabigatran-related bleeding— whether from trauma or as an adverse effect—may be more difficult to treat than warfarin-related bleeding."

Couple this safety issue with the promotion of Pradaxa in the media as a "super pill" and a "revolutionary drug" (see "Bad Journalism or Bad Pharma?") and you end up with a real public safety issue that patients should be concerned about. BI itself stoked this Pradaxa-mania (read, for example, "BI Masters the Art of WOM through Its 'Parrots,' er, Spokespersons" and "Full BOEHR(inger) Social Media Reporting of RELY Trial Results").

Sadly, Woodcock may have heard from "patient advocates" paid by pharma companies to testify before the FDA, but who advocates for the patients harmed by drugs like Pradaxa? Their stories are locked in the FDA's adverse event database, which is not generally cited during drug approval Hearings at the FDA.

Not to mention the impact of DTC advertising on the public's willingness to accept greater risk:

Monday, August 20, 2012

Certifying Prescription Grade Smartphone Medical Apps

An article in yesterday's NYT focused on what I call "Prescription Grade Smartphone Medical Apps." The article said the idea of such apps "excites some people in the health care industry, who see them as a starting point for even more sophisticated applications that might otherwise never be built" (read the article here).

"But unlike a 99-cent game, apps dealing directly with medical care cannot be introduced to the public with bugs that will be fixed later. The industry is still grappling with how to ensure quality and safety." I have written about this issue before, although for apps created by the pharma industry and not "Prescription Grade" apps. See, for example:

Happtique, in July 2012, released a draft of standards that it will be using to certify medical, health, and fitness apps under Happtique’s App Certification Program. The purpose of the program is to help users identify apps that meet high operability, privacy, and security standards and are based on reliable content. You can find the Happtique certification draft standards attached to this post.

The Happtique Certification Standards include these categories:

Content Standard C1 states: "The app is based on one or more credible information sources such as an accepted protocol, published guidelines, evidence-based practice, peer-reviewed journal, etc.

Performance Requirements for Standard C1

But more troubling than the lack of documentation regarding content, is the accuracy of the apps software. Happtique Certification Security Standards address some of my concerns.

Security Standard S6 states: "The app owner has a mechanism to notify end users about apps that are banned or recalled by the app owner or any regulatory entity (e.g., FDA, FTC, FCC)."

Performance Requirements for Standard S6

"But unlike a 99-cent game, apps dealing directly with medical care cannot be introduced to the public with bugs that will be fixed later. The industry is still grappling with how to ensure quality and safety." I have written about this issue before, although for apps created by the pharma industry and not "Prescription Grade" apps. See, for example:

- Some Unregulated Physician Smartphone Apps May Be Buggy

- FDA Mobile Regulatory Fear Mongering by PhRMA

- Be Aware of What's Behind a Pharma Mobile App: Disclaimers Only Tell Part of the Story

Happtique, in July 2012, released a draft of standards that it will be using to certify medical, health, and fitness apps under Happtique’s App Certification Program. The purpose of the program is to help users identify apps that meet high operability, privacy, and security standards and are based on reliable content. You can find the Happtique certification draft standards attached to this post.

The Happtique Certification Standards include these categories:

- App Operability Standards

- App Privacy Standards

- App Security Standards

- App Content Standards

Content Standard C1 states: "The app is based on one or more credible information sources such as an accepted protocol, published guidelines, evidence-based practice, peer-reviewed journal, etc.

Performance Requirements for Standard C1

- C1.01 If the app is based on content from a recognized source (e.g., guidelines from a public or private entity), documentation (e.g., link to journal article, medical textbook citation) about the information source is provided.

- C1.02 If the app is based on content other than from a recognized source, documentation about how the content was formulated is provided, including information regarding its relevancy and reliability

But more troubling than the lack of documentation regarding content, is the accuracy of the apps software. Happtique Certification Security Standards address some of my concerns.

Security Standard S6 states: "The app owner has a mechanism to notify end users about apps that are banned or recalled by the app owner or any regulatory entity (e.g., FDA, FTC, FCC)."

Performance Requirements for Standard S6

- S6.01 In the event that an app is banned or recalled, a mechanism or process is in place to notify all users about the ban or recall and render the app inoperable.

- S6.02 In the event that the app constitutes a medical device (e.g., 510(k)) or is regulated by the FDA in any other capacity, the app owner has a policy and a mechanism in place to comply with any and all applicable rules and regulations for purposes of handling all aspects of a product notification or recall, including all corrections and removals.

Saturday, July 7, 2012

Positive or Not, Pediatric Drug Trials Pay Off: Cymbalta and Oxycontin Case Studies

Very few people may know that drug companies can get an additional six months of market exclusivity from FDA as an inducement for them to study the efficacy and safety of drugs in children. Fewer people realize that no matter what the outcome of such tests, FDA will still grant the additional 6 months of exclusivity before generic copies of the tested drug can be introduced.

A case in point is Cymbalta, an antidepressant marketed by Lilly.

As reported in the Wall Street Journal (here), Cymbalta will have an additional six months of U.S. market exclusivity -- through December 2013 -- because the company studied the drug's effects on children. "Lilly said, however, that it won't seek regulatory approval to market Cymbalta for pediatric use because study results were inconclusive regarding Cymbalta's efficacy in children."

Cymbalta is the "duct tape" of drugs; i.e., it has many approved indications for use in adults.

Cymbalta was originally approved in 2004 for adults with major depression. Later the FDA granted Lilly approval to market Cymbalta for treating nerve pain in diabetics, GAD (ie, "generalized anxiety disorder"; see "eGAD! How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Cymbalta!") and fibromyalgia, a condition characterized by chronic fatigue and muscle and joint pain.

With each new indication comes the potential to increase sales significantly. In 2010, for example, Cymbalta was approved for chronic lower back and knee pain, an indication that may have increased sales by $500 Million, a 16% increase over the $3.07 Bn in sales for Cymbalta in 2009 (read, for example, "Cymbalta: A Sweet ROI for Chronic Pain Indication").

But a 16% increase in sales is paltry compared with a 50% increase in sales that is possible when the FDA approves a drug for use in children under the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act, a statute that created the incentive for drug makers to test the products in young patients. For Lilly, a 6-month extension of market exclusivity for Cymbalta could give Lilly more than a $2 Billion windfall (in April, 2012, Lilly reported that first-quarter sales of Cymbalta rose 23% to $1.11 billion).

I'm sure the intent of the law was to make it possible for physicians to prescribe drugs for children based on evidence that the drugs worked in children. To offset the cost to drug companies to run trails to prove efficacy, Congress allowed 6 months of additional exclusivity during which those costs could be recouped. In the case of Cymbalta, children do not benefit and Lilly more than recoups the cost of pediatric trials, which involve perhaps only a few hundred subjects.

Purdue Pharma, however, claimed it lacked resources in 2004 when it abandoned a pediatric Oxycontin clinical trial requested by the FDA. Only now -- when Oxycontin is a mere year away from losing market exclusivity -- is Purdue pursing such a trial (see "After Delay, OxyContin’s Use in Young Is Under Study"). Sales of Oxycontin reached $1.7 billion (in the U.S.?) in 2004.

It is too soon to know if the Oxycontin pediatric trial will demonstrate any effectiveness in treating children under 12. One thing that is certain, however, is that street use of Oxycontin by children and young adults is deadly. If extended market exclusivity can help prevent illegal diversion of even cheaper generic versions of Oxycontin, then I am all for it no matter what the clinical trail results!

A case in point is Cymbalta, an antidepressant marketed by Lilly.

As reported in the Wall Street Journal (here), Cymbalta will have an additional six months of U.S. market exclusivity -- through December 2013 -- because the company studied the drug's effects on children. "Lilly said, however, that it won't seek regulatory approval to market Cymbalta for pediatric use because study results were inconclusive regarding Cymbalta's efficacy in children."

Cymbalta is the "duct tape" of drugs; i.e., it has many approved indications for use in adults.

Cymbalta was originally approved in 2004 for adults with major depression. Later the FDA granted Lilly approval to market Cymbalta for treating nerve pain in diabetics, GAD (ie, "generalized anxiety disorder"; see "eGAD! How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Cymbalta!") and fibromyalgia, a condition characterized by chronic fatigue and muscle and joint pain.

With each new indication comes the potential to increase sales significantly. In 2010, for example, Cymbalta was approved for chronic lower back and knee pain, an indication that may have increased sales by $500 Million, a 16% increase over the $3.07 Bn in sales for Cymbalta in 2009 (read, for example, "Cymbalta: A Sweet ROI for Chronic Pain Indication").

But a 16% increase in sales is paltry compared with a 50% increase in sales that is possible when the FDA approves a drug for use in children under the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act, a statute that created the incentive for drug makers to test the products in young patients. For Lilly, a 6-month extension of market exclusivity for Cymbalta could give Lilly more than a $2 Billion windfall (in April, 2012, Lilly reported that first-quarter sales of Cymbalta rose 23% to $1.11 billion).

I'm sure the intent of the law was to make it possible for physicians to prescribe drugs for children based on evidence that the drugs worked in children. To offset the cost to drug companies to run trails to prove efficacy, Congress allowed 6 months of additional exclusivity during which those costs could be recouped. In the case of Cymbalta, children do not benefit and Lilly more than recoups the cost of pediatric trials, which involve perhaps only a few hundred subjects.

Purdue Pharma, however, claimed it lacked resources in 2004 when it abandoned a pediatric Oxycontin clinical trial requested by the FDA. Only now -- when Oxycontin is a mere year away from losing market exclusivity -- is Purdue pursing such a trial (see "After Delay, OxyContin’s Use in Young Is Under Study"). Sales of Oxycontin reached $1.7 billion (in the U.S.?) in 2004.

It is too soon to know if the Oxycontin pediatric trial will demonstrate any effectiveness in treating children under 12. One thing that is certain, however, is that street use of Oxycontin by children and young adults is deadly. If extended market exclusivity can help prevent illegal diversion of even cheaper generic versions of Oxycontin, then I am all for it no matter what the clinical trail results!

Labels:

Cymbalta,

FDA,

Lilly,

Oxycontin,

pediatrics,

Purdue Pharma

Wednesday, June 27, 2012

Drug Ads & Coupons: Who's the Decider? The Patient, the Physician, or the FDA?

The FDA is concerned that the use of sales promotions such as free trial offers, discounts, money-back guarantees, and rebates in direct-to-consumer (DTC) prescription drug ads "artificially enhance consumers' perceptions of the product's quality" while also resulting in an "unbalanced or misleading impression of the product's safety." To test whether or not this is true, the FDA will soon start yet another study focused on Rx print ads: "Effect of Promotional Offers in Direct-to-Consumer Prescription Drug Print Advertisements on Consumer Product Perceptions" (see Federal Register Notice archived here).

[I recently posted about another planned FDA study to determine if disease awareness information in branded ads confuses consumers. See FDA Concerned About Product (eg, Lyrica) Ads That are Too "Educational"]

The history of this study is long and mysterious. I first blogged about it 2006; read "FDA, Coupons, and Sleep Aid DTC Ads." Shortly after that the Federal Register notice regarding the study was "yanked" (see "FDA Backs Down on Coupon Study"). Also, the Advertising Age and Wall Street Journal articles cited in those posts can no longer be found in the archives.

In September, 2011, however, the proposed study re-emerged in the Federal Register (here). Whatever happened between 2006 and 2011 is anybody's guess, but I assume that the Bush era FDA leaders axed the proposed study when they learned of it. By September, 2011, these people were on the way out and the door was open again to propose the study anew.

Anyhoo, I want to focus here on comments that PhRMA made in response to the proposal. Alexander Gaffney (@AlecGaffney), Health wonk and writer of news for @RAPSorg, summarized the general attitude of PhRMA (see "US Regulators Move Ahead With Planned Study on DTC Marketing"):

I dug a little deeper into PhRMA comments (here) and was surprised to learn that PhRMA's position is that "it is the physician, not the patient (my emphasis), who ultimately must decide whether the benefits of the advertised drug outweigh its risks for any particular patient." Thus, says PhRMA, "the risks of 'misperceptions' ... should be even lower [PhRMA's emphasis] for prescription drugs than for experience goods [i.e., a product or service where product characteristics, such as quality or price are difficult to observe in advance, but these characteristics can be ascertained upon consumption] because any potential misperception, of necessity, will be quickly corrected prior to use through consultation with the patient's treating physician."

This is a very paternalistic POV in this day and age of social media and patient empowerment. Actually, it is the old "learned intermediary" defense that the drug industry often raises (in the past, less so these days) to shield itself from blame when things go wrong.

FDA must respond to comments submitted, but I couldn't find a direct response to PhRMA's comments cited above. I did find, however, the following comments and FDA's response that addressed the issue of the patient-physician relationship generally:

[I recently posted about another planned FDA study to determine if disease awareness information in branded ads confuses consumers. See FDA Concerned About Product (eg, Lyrica) Ads That are Too "Educational"]

The history of this study is long and mysterious. I first blogged about it 2006; read "FDA, Coupons, and Sleep Aid DTC Ads." Shortly after that the Federal Register notice regarding the study was "yanked" (see "FDA Backs Down on Coupon Study"). Also, the Advertising Age and Wall Street Journal articles cited in those posts can no longer be found in the archives.

In September, 2011, however, the proposed study re-emerged in the Federal Register (here). Whatever happened between 2006 and 2011 is anybody's guess, but I assume that the Bush era FDA leaders axed the proposed study when they learned of it. By September, 2011, these people were on the way out and the door was open again to propose the study anew.

Anyhoo, I want to focus here on comments that PhRMA made in response to the proposal. Alexander Gaffney (@AlecGaffney), Health wonk and writer of news for @RAPSorg, summarized the general attitude of PhRMA (see "US Regulators Move Ahead With Planned Study on DTC Marketing"):

In its statement to FDA, PhRMA wrote it was “concerned that the study, as currently envisioned, will not yield information that is relevant to FDA’s regulatory responsibilities to ensure that DTC advertising is truthful, accurate and balanced.”PhRMA: The Physician is the Decider

“Although the study may provide interesting information about the effect of promotional offers on consumer attitudes toward a brand,” explained PhRMA, “it likely will provide little information on whether promotional offers create or contribute to false or misleading advertising, particularly under real-world circumstances or whether additional regulatory requirements are warranted.”

I dug a little deeper into PhRMA comments (here) and was surprised to learn that PhRMA's position is that "it is the physician, not the patient (my emphasis), who ultimately must decide whether the benefits of the advertised drug outweigh its risks for any particular patient." Thus, says PhRMA, "the risks of 'misperceptions' ... should be even lower [PhRMA's emphasis] for prescription drugs than for experience goods [i.e., a product or service where product characteristics, such as quality or price are difficult to observe in advance, but these characteristics can be ascertained upon consumption] because any potential misperception, of necessity, will be quickly corrected prior to use through consultation with the patient's treating physician."

This is a very paternalistic POV in this day and age of social media and patient empowerment. Actually, it is the old "learned intermediary" defense that the drug industry often raises (in the past, less so these days) to shield itself from blame when things go wrong.

FDA must respond to comments submitted, but I couldn't find a direct response to PhRMA's comments cited above. I did find, however, the following comments and FDA's response that addressed the issue of the patient-physician relationship generally:

(Comment 22) Two comments mentioned that the study does not assess how consumer perceptions of product risks and benefits are translated into a discussion with their health care provider. One comment stated that because these products can only be purchased after a discussion with a health care provider, the study be redesigned so that consumer perceptions are measured after a discussion with a health care provider.

(Response) We concur that this study does not address behaviors, such as how ad perceptions are translated into a discussion with a health care provider. As noted previously, one purpose of DTC advertising is to motivate consumers to engage in a discussion with their health care provider about health concerns. Another purpose, supported by research findings (Refs. 20 and 21), is to increase awareness of available treatments. DTC advertising does not exist solely in the confines of a doctor's office; rather, DTC advertising targets consumers outside of a doctor's office, with the goal of prompting consumers to ask their physicians about the product. In deciding whether or not to discuss a particular product with their health care provider, consumers presumably are engaging in some sort of judgment about the product being promoted. Therefore, clear communication of risks and benefits is needed for consumers before a consultation with a physician, and it is valid to measure these impressions.

Sunday, June 24, 2012

FDA Concerned About Product (eg, Lyrica) Ads That are Too "Educational"

In a recent Federal Register notice (find it here), FDA outlined a study it plans to do to determine if disease awareness information in branded ads confuses consumers; i.e., if consumers confuse educational information about a disease with specific product claims approved by the FDA. As usual, FDA will only study print ads -- not Internet-based ads.

"Sponsors [pharmaceutical companies] may choose to include disease information in their full product promotions," says FDA. "Such information is designed to educate the patient about his or her disease condition. However, in some cases a full description of the medical condition may include information about specific health outcomes that are not part of a drug’s approved indication... When broad disease information accompanies or is included in an ad for a specific drug," says the FDA, "consumers may mistakenly assume that the drug will address all of the potential consequences of the condition mentioned in the ad by making inferences that go beyond what is explicitly stated in an advertisement."

FDA cites as an example a hypothetical ad that mentions "diabetic retinopathy," which is damage to the eye's retina that occurs with long-term diabetes. "...the mention of diabetic retinopathy in an advertisement for a drug that lowers blood glucose may lead consumers to infer that the drug will prevent diabetic retinopathy, even if no direct claim is made. The advertisement may imply broader indications for the promoted drug than are warranted, leading consumers to infer effectiveness of the drug beyond the indication for which it was approved."

I couldn't find a diabetes-related print drug ad that mentioned "diabetic retinopathy," but I did find one in today's Parade magazine that informed me that "Diabetes Damages Nerves." That ad (shown below) promotes Pfizer's drug Lyrica, which is indicated for the treatment of "Diabetic Nerve Pain." It is NOT indicated to prevent nerve damage caused by diabetes.

What I see when quickly glancing at this ad is "DIABETES DAMAGES NERVES" (all caps), then "PAIN," (also all caps) and, finally, "LYRICA" (also all caps). If I were a typical consumer with diabetes, I might think that LYRICA prevents damage to my nerves, which would be an incorrect assumption.

"Sponsors [pharmaceutical companies] may choose to include disease information in their full product promotions," says FDA. "Such information is designed to educate the patient about his or her disease condition. However, in some cases a full description of the medical condition may include information about specific health outcomes that are not part of a drug’s approved indication... When broad disease information accompanies or is included in an ad for a specific drug," says the FDA, "consumers may mistakenly assume that the drug will address all of the potential consequences of the condition mentioned in the ad by making inferences that go beyond what is explicitly stated in an advertisement."

FDA cites as an example a hypothetical ad that mentions "diabetic retinopathy," which is damage to the eye's retina that occurs with long-term diabetes. "...the mention of diabetic retinopathy in an advertisement for a drug that lowers blood glucose may lead consumers to infer that the drug will prevent diabetic retinopathy, even if no direct claim is made. The advertisement may imply broader indications for the promoted drug than are warranted, leading consumers to infer effectiveness of the drug beyond the indication for which it was approved."

I couldn't find a diabetes-related print drug ad that mentioned "diabetic retinopathy," but I did find one in today's Parade magazine that informed me that "Diabetes Damages Nerves." That ad (shown below) promotes Pfizer's drug Lyrica, which is indicated for the treatment of "Diabetic Nerve Pain." It is NOT indicated to prevent nerve damage caused by diabetes.

What I see when quickly glancing at this ad is "DIABETES DAMAGES NERVES" (all caps), then "PAIN," (also all caps) and, finally, "LYRICA" (also all caps). If I were a typical consumer with diabetes, I might think that LYRICA prevents damage to my nerves, which would be an incorrect assumption.

BTW, the ad also says "Lyrica is believed to work on these damaged nerves." What does that mean? Does Lyrica work on repairing the nerves? or does it work on shutting down the nerves so you don't feel pain? And, what does "believed" mean? It's all very mysterious!This ad probably is not the best example of an ad that FDA has in mind -- it was just the best example I could find at the moment. I'll have to buy a few more consumer magazines to find other, more relevant examples. If you know of one, please point it out to me.

Labels:

Disease awareness,

FDA,

Lyrica,

Pfizer,

print ads,

Regulation

Friday, June 22, 2012

Abbott's Anti-Biosimilar Stance is Anti-Consumer

The pharmaceutical industry often wonders why it has such a bad reputation with consumers -- nearly as bad as the tobacco industry -- considering it saves lives, as opposed to the tobacco industry, which ends lives. Well, to understand why this is so, you need look no further than actions such as Abbott's April 2, 2012 citizen's petition against FDA approval of biosimilars (read more about that and find a copy of the petition here: "Abbott Labs Petitions FDA to Disallow Biosimilars").

According to the FDA (here):

"If the challenge succeeds," says WSJ, "less-expensive versions of complex biologic drugs couldn't go on sale in the U.S. for years, and consumers may never have access to facsimiles of existing treatments such as Abbott's rheumatoid arthritis therapy Humira, which had $3.4 billion in U.S. sales last year and is projected to be the world's No. 1-selling drug this year."

Abbott "contends that its drug isn't copyable under the law, because regulators would need its Humira trade secrets to approve a biosimilar and would thereby violate its constitutional rights. The company said it is protecting an investment of 'massive amounts of capital' and the 'great risk' it took developing the drug. In fact, Abbott contends that no biologic approved before the law was signed should be considered copyable."

"Critics of Abbott's position say that the argument lacks merit and is anticompetitive, and that trade secrets aren't necessary to prove that a copy will work like the original. The critics also contend Abbott is backtracking on its support for the legislation and ignoring the potential impact on the country's spiraling health-care spending."

Considering that Abbott Labs will soon have the NUMBER 1 selling drug in the world (see below) -- taking the crown from Pfizer's LIPITOR -- it makes perfect sense that Abbott should act NOW to protect its patented money-maker, years before it finds itself in the not-so-envious position of Pfizer, which fought on even after the bell rang on Lipitor (see "Pfizer Throws In the Lipitor Marketing Towel"). Note: Humira's U.S. patent expires in December 2016

With the filing of this petition, Abbott Labs may also take on another "crown" previously held by Pfizer -- the world's most hated pharmaceutical company. Good luck with that Abbott.

Booming Biologics

Abbott, however, is just the "poster boy" (or "patsy") chosen by the drug industry to take the shots by filing this petition, which really speaks for the entire industry. Patented biologics is a big business and represents the future of the pharmaceutical industry.

According to the WSJ, biologics "had $74.8 billion in U.S. sales last year, up 8.3% from the previous year, according to the IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics. This year, seven of the 10 top-selling drugs will be biologics, with a total of $50.4 billion in world-wide sales, according to EvaluatePharma, which predicts that Humira will be No. 1 with $9.3 billion in world-wide sales."

According to the FDA (here):

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Affordable Care Act), signed into law by President Obama on March 23, 2010, amends the Public Health Service Act (PHS Act) to create an abbreviated licensure pathway for biological products that are demonstrated to be “biosimilar” to or “interchangeable” with an FDA-licensed biological product. This pathway is provided in the part of the law known as the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCI Act). Under the BPCI Act, a biological product may be demonstrated to be “biosimilar” if data show that, among other things, the product is “highly similar” to an already-approved biological product.The law protects the original biologic drug from copies for 12 years after approval.

"If the challenge succeeds," says WSJ, "less-expensive versions of complex biologic drugs couldn't go on sale in the U.S. for years, and consumers may never have access to facsimiles of existing treatments such as Abbott's rheumatoid arthritis therapy Humira, which had $3.4 billion in U.S. sales last year and is projected to be the world's No. 1-selling drug this year."

Abbott "contends that its drug isn't copyable under the law, because regulators would need its Humira trade secrets to approve a biosimilar and would thereby violate its constitutional rights. The company said it is protecting an investment of 'massive amounts of capital' and the 'great risk' it took developing the drug. In fact, Abbott contends that no biologic approved before the law was signed should be considered copyable."

"Critics of Abbott's position say that the argument lacks merit and is anticompetitive, and that trade secrets aren't necessary to prove that a copy will work like the original. The critics also contend Abbott is backtracking on its support for the legislation and ignoring the potential impact on the country's spiraling health-care spending."

Considering that Abbott Labs will soon have the NUMBER 1 selling drug in the world (see below) -- taking the crown from Pfizer's LIPITOR -- it makes perfect sense that Abbott should act NOW to protect its patented money-maker, years before it finds itself in the not-so-envious position of Pfizer, which fought on even after the bell rang on Lipitor (see "Pfizer Throws In the Lipitor Marketing Towel"). Note: Humira's U.S. patent expires in December 2016

With the filing of this petition, Abbott Labs may also take on another "crown" previously held by Pfizer -- the world's most hated pharmaceutical company. Good luck with that Abbott.

Booming Biologics

Abbott, however, is just the "poster boy" (or "patsy") chosen by the drug industry to take the shots by filing this petition, which really speaks for the entire industry. Patented biologics is a big business and represents the future of the pharmaceutical industry.

According to the WSJ, biologics "had $74.8 billion in U.S. sales last year, up 8.3% from the previous year, according to the IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics. This year, seven of the 10 top-selling drugs will be biologics, with a total of $50.4 billion in world-wide sales, according to EvaluatePharma, which predicts that Humira will be No. 1 with $9.3 billion in world-wide sales."

Labels:

Abbott,

biosimilar,

FDA,

Humira,

Patent Expiry,

Regulation

Friday, May 25, 2012

Is There a Doctor in the House? FDA Bad Ad Program is Designed for You. Not So Much for Me!

Two days ago, I sent an email to FDA's "Bad Ad" program (email addr: BadAd@fda.hhs.gov) to cite a Pfizer iPhone App as a "Bad Ad" (see "Recipes 2 Go: Pfizer's LIPITOR-Branded iPhone App. Is It an Ad FDA Should Review?" for background). For the record, here's a screen shot of the email I sent (click on it for an enlarged view):

A minute later, I received an acknowledgement email from the FDA that started with "Thank you for taking the time to alert us to potentially misleading promotion," but ended with "If you are not a healthcare provider, please refer to the OPDP website for instructions on how to submit a complaint, or call (301) 796-1200." I was confused, so I called the number and left a message.

Today, Olga Salis, OPDP Senior Project Manager, called me back to explain the Bad Ad complaint process. It appears that "healthcare professionals" (i.e., mostly physicians) can submit complaints about ads via email whereas ordinary citizens such as myself MUST use snail mail; i.e., send a physical letter to FDA/CDER/OPDP, 5901-B Ammendale Rd, Beltsville, MD 20705-1266. This distinction is not clear from the information provided on the Bad Ad page here.

It's OBVIOUS that the FDA does not want to be bothered or flooded by consumer complaints because it is not making it easy for consumers to submit complaints. Who knows if FDA would have done anything with my complaint had I not called. As it is, it may take OPDP THREE months to respond or take action on my complaint, "if it has merit."

NOTE: FDA receives complaints from three sources: Healthcare Professionals (HCPs), Consumers, and "representatives of regulated industry" (ie, pharma companies ratting out their competitors). The "pharma" group of complaints was the most credible -- 58% of those complaints were deemed worthy for "comprehensive review," whereas 46% of HCP complaints and only 21% of consumer complaints made the cut (see figure below and also here):

I will followup with a written letter sent to OPDP. However, I encourage any healthcare professional reading this blog to download the Pfizer iPhone app in question and if you agree with me that it is worthy of a "bad ad" complaint to the FDA, then all you have to do is send an email to BadAd@fda.hhs.gov. Easy for you, not so much for me :-(

A minute later, I received an acknowledgement email from the FDA that started with "Thank you for taking the time to alert us to potentially misleading promotion," but ended with "If you are not a healthcare provider, please refer to the OPDP website for instructions on how to submit a complaint, or call (301) 796-1200." I was confused, so I called the number and left a message.

Today, Olga Salis, OPDP Senior Project Manager, called me back to explain the Bad Ad complaint process. It appears that "healthcare professionals" (i.e., mostly physicians) can submit complaints about ads via email whereas ordinary citizens such as myself MUST use snail mail; i.e., send a physical letter to FDA/CDER/OPDP, 5901-B Ammendale Rd, Beltsville, MD 20705-1266. This distinction is not clear from the information provided on the Bad Ad page here.

It's OBVIOUS that the FDA does not want to be bothered or flooded by consumer complaints because it is not making it easy for consumers to submit complaints. Who knows if FDA would have done anything with my complaint had I not called. As it is, it may take OPDP THREE months to respond or take action on my complaint, "if it has merit."

NOTE: FDA receives complaints from three sources: Healthcare Professionals (HCPs), Consumers, and "representatives of regulated industry" (ie, pharma companies ratting out their competitors). The "pharma" group of complaints was the most credible -- 58% of those complaints were deemed worthy for "comprehensive review," whereas 46% of HCP complaints and only 21% of consumer complaints made the cut (see figure below and also here):

Source: pharmamkting.blogspot.com via Pharma on Pinterest

I will followup with a written letter sent to OPDP. However, I encourage any healthcare professional reading this blog to download the Pfizer iPhone app in question and if you agree with me that it is worthy of a "bad ad" complaint to the FDA, then all you have to do is send an email to BadAd@fda.hhs.gov. Easy for you, not so much for me :-(

Wednesday, May 23, 2012

Recipes 2 Go: Pfizer's LIPITOR-Branded iPhone App. Is It an Ad FDA Should Review?

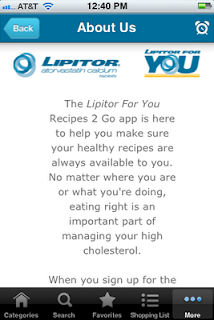

I just learned that Pfizer has developed an iPhone/iPad app that promotes LIPITOR, the drug company's off-patent lipid-lowering drug. The app is "Recipes 2 Go." It is the first pharmaceutical app that I know of that promotes a prescription drug.

Here's what the promo screen on iTunes looks like (click on it for an enlarged view):

The description -- shown here in its entirety -- mentions LIPITOR and the FDA-approved indication, which is managing high cholesterol.

Is This an FDA-regulated Drug Ad?

My question: Does this iTunes page qualify as an prescription drug ad that must comply with FDA regulations regarding fair balance (ie, Important Safety Information or ISI)? If it does qualify, then it violates FDA regulations because the page does not include ANY fair balance or a link to the full prescribing information.

Did Pfizer submit this page to FDA for regulatory review? Did it submit the page to its own MLR (medical/legal/regulatory) people?

I downloaded the app to my iPhone and found the side effect/fair balance information plus a link to the "full prescribing" information on the very bottom of the "About Us" screen. Here's what the screen looks like:

Only when you scroll down to the next screen do you see the notice "Scroll down to see Important Safety Information," which appears about 14 screens further down! Whew! That's a lot of scrolling!

The multi-page End-User Agreement (dated April 20, 2012) should be read carefully. For one thing, it states that "NO STATEMENTS MADE IN THIS SOFTWARE HAVE BEEN EVALUATED BY THE FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION."

To which I say, Why Not? The FDA should definitely take a look at this app and decide if it complies with regulations.

Because this app does not present the ISI where it can easily be found (and not at all on the iTunes promo page), I gave it only a single star rating on iTunes :-)

Here's what the promo screen on iTunes looks like (click on it for an enlarged view):

The description -- shown here in its entirety -- mentions LIPITOR and the FDA-approved indication, which is managing high cholesterol.

Is This an FDA-regulated Drug Ad?

My question: Does this iTunes page qualify as an prescription drug ad that must comply with FDA regulations regarding fair balance (ie, Important Safety Information or ISI)? If it does qualify, then it violates FDA regulations because the page does not include ANY fair balance or a link to the full prescribing information.

Did Pfizer submit this page to FDA for regulatory review? Did it submit the page to its own MLR (medical/legal/regulatory) people?

I downloaded the app to my iPhone and found the side effect/fair balance information plus a link to the "full prescribing" information on the very bottom of the "About Us" screen. Here's what the screen looks like:

Only when you scroll down to the next screen do you see the notice "Scroll down to see Important Safety Information," which appears about 14 screens further down! Whew! That's a lot of scrolling!

The multi-page End-User Agreement (dated April 20, 2012) should be read carefully. For one thing, it states that "NO STATEMENTS MADE IN THIS SOFTWARE HAVE BEEN EVALUATED BY THE FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION."

To which I say, Why Not? The FDA should definitely take a look at this app and decide if it complies with regulations.

Because this app does not present the ISI where it can easily be found (and not at all on the iTunes promo page), I gave it only a single star rating on iTunes :-)

Labels:

Apps,

Cholesterol,

Drug Safety,

FDA,

iPhone,

Lipitor,

Pfizer

Shire Seeks to Maintain YouTube "Loophole" in FDA's Draft Guidelines for TV Ads

FDA has received several comments from the pharmaceutical industry regarding the agency's "Draft Guidance for Industry Direct-to-Consumer Television Advertisements." In past posts I reviewed comments from PhRMA (the drug industry U.S. trade association) and Sanofi (see here and here). In this post, I report on comments made by Shire (find Shire's comments here).

Shire, like Sanofi, Novo Nordisk and Boehringer Ingelheim (BI), believes that submission of a final recorded version of a TV ad for FDA approval prior to being aired would be "burdensome." Shire specifically cites the optional two-step process FDA suggested; i.e., first submit an annotated storyboard and then a final recorded version of the ad. "This sequential two-submission process would double the time and resource burden on sponsors as well as the Agency," says Shire.

FDA and the drug industry continue to see no need to issue any mandatory or even voluntary guidelines specifically for drug promotion via the Internet. Shire points out, for example, that there already is an "advisory review process" that applies to video advertisements disseminated through "other viewing platforms' (i.e., the Internet). That process (see here) says "a sponsor may voluntarily submit advertisements to FDA for comment prior to publication."

However, if "dissemination" is defined according to Shire's rules, then it is possible for a drug company to run a video ad on YouTube months before it airs the same ad on TV without having to submit anything to the FDA for review -- the current "advisory review process" that Shire refers to is voluntary.

As part of that process (e.g., submission of static storyboards for video ads), FDA estimates that "approximately 2 hours on average would be needed per submission, including the time it takes to prepare, assemble, and copy the necessary information." Compared to that, the creation of "final filmed" versions of TV ads is indeed a significant burden on sponsors. However, since FDA's new guidelines are specifically aimed at products with significant safety concerns, it "behooves" the drug industry to carry that "burden" in the interest of patient safety, IMHO.

Shire, like Sanofi, Novo Nordisk and Boehringer Ingelheim (BI), believes that submission of a final recorded version of a TV ad for FDA approval prior to being aired would be "burdensome." Shire specifically cites the optional two-step process FDA suggested; i.e., first submit an annotated storyboard and then a final recorded version of the ad. "This sequential two-submission process would double the time and resource burden on sponsors as well as the Agency," says Shire.

Serial OPDP Review Blues

BI also mentioned the "burden" of a two-step process in its comments to the FDA (find them here). But BI was referring to the need to resubmit a new version of the ad after receiving critical comments from the FDA concerning the first version submitted for review.

"BIPI is concerned with the incremental time and cost that would be incurred by sponsors to routinely produce and submit multiple broadcasts for the purpose of OPDP [FDA's Office of Prescription Drug Promotion] pre-dissemination review," says BI. "BIPI is similarly concerned that the repeated submissions of storyboards to capture serial sets of OPDP suggestions (i.e., the submission of modified storyboards for advisory comments following integration of initial advisory comments) would greatly increase the time, if not the cost, of producing DTC broadcast ads."

BI says that it "behooves sponsors to ensure storyboards submitted for advisory comments are representative of the final ad and to ensure that the Agency's comments are incorporated into the filmed version." In other words, BI suggests FDA just look at storyboards and trust that the sponsor will create a final "filmed" ad that is revised according to FDA comments.Shire, however, was the only pharma company to point out a "loophole" that I revealed on Pharma Marketing Blog in March (see "A Loophole (?) in New FDA Guidance on Pre-Dissemination Review of TV Direct-to-Consumer Ads"). In that post, I said:

"FDA does not define what exactly it means by 'dissemination.' Perhaps it has defined this term elsewhere in it regulatory archives, but I assume in this case it means airing the ad on mass market TV. Does that include uploading the video to YouTube? A drug company could upload a video of a pre-approved ad to YouTube at the same time that it submits the video to FDA for 'pre-dissemination' review. The video can then be embedded in the drug.com website or promoted via Twitter."Shire pointed out the same lack of clarity in its comments. "...there has been increasing availability and use of vehicles other than broadcast TV to present video advertising, such as on-demand viewing via the Internet," says Shire. "Shire recommends that FDA affirm that the scope of the guidance includes only DTC advertisements disseminated through broadcast television."

FDA and the drug industry continue to see no need to issue any mandatory or even voluntary guidelines specifically for drug promotion via the Internet. Shire points out, for example, that there already is an "advisory review process" that applies to video advertisements disseminated through "other viewing platforms' (i.e., the Internet). That process (see here) says "a sponsor may voluntarily submit advertisements to FDA for comment prior to publication."

However, if "dissemination" is defined according to Shire's rules, then it is possible for a drug company to run a video ad on YouTube months before it airs the same ad on TV without having to submit anything to the FDA for review -- the current "advisory review process" that Shire refers to is voluntary.

Monday, May 21, 2012

PhRMA Demands that FDA "Cabin" Its Discretion to Regulate DTC Ads

In a 20-page comment submitted to the FDA on May 14, 2012, the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), advised the FDA to "proceed cautiously and in a manner that fully protects the free speech rights of advertisers and patients" with regard to the agency's recent Draft Guidance for Industry on Direct-to-Consumer (DTC) Television Advertisements."

Recall that the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007 (FDAAA) gives FDA the authority to ". . . require the submission of any television advertisement for a drug . . . not later than 45 days before dissemination of the television advertisement" (see "Draft FDA Guidance on PreDissemination Review of TV Direct-to-Consumer Ads").

In its comments, PhRMA uses the word "cabin" as a verb, as in "clearly defined standards that cabin the reviewing official's 'unbridled discretion'" and "objective standards to cabin FDA's discretion."

Why does PhRMA want to banish FDA to a "cabin" in the woods as far it's discretion to pre-review DTC ads is concerned?

PhRMA is itching to challenge FDA's authority to regulate DTC advertising in front of the Supreme Court, which is cited several times in PhRMA's comments. For example, PhRMA reminded the FDA (as if that was necessary) that the Supreme Court "recently affirmed that '[s]peech in aid of pharmaceutical marketing .... is a form of expression protected by the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment.' Thus," says PhRMA, "when the FDA restricts the speech of pharmaceutical manufacturers and other regulated entities, the restrictions are subject to scrutiny under the First Amendment."

But the Supreme Court Court is not likely to scrutinize "informal guidance," which is not legally binding. Therefore, PhRMA is pushing the FDA to issue regulations, which carry the weight of law. "Regulations that unduly burden truthful, non-misleading commercial speech about a lawful product," says PhRMA, "hinder consumer choice ... and rarely survive constitutional scrutiny."

Of course, FDA wants to prevent "misleading" drug ads from being aired. Right now, however, it can only cite ads as "misleading" AFTER they have already been aired.

I'm not going to delve into the legal arguments that PhRMA puts forth. You can read them yourself here. I just find it interesting that the drug industry is pushing FDA to stop issuing non-binding guidances in this case as well as in the case of social media (see "WLF & Pfizer Ask Court to Block FDA Guidance on Social Media"). I also like how PhRMA uses "cabin" as a verb, hence the cabin image that accompanies this post.

Hat Tip to @AlecGaffney for alerting me to the publication of PhRMA's comments in the Federal Register, where "occasionally interesting reading [is] to be had."

Recall that the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007 (FDAAA) gives FDA the authority to ". . . require the submission of any television advertisement for a drug . . . not later than 45 days before dissemination of the television advertisement" (see "Draft FDA Guidance on PreDissemination Review of TV Direct-to-Consumer Ads").

In its comments, PhRMA uses the word "cabin" as a verb, as in "clearly defined standards that cabin the reviewing official's 'unbridled discretion'" and "objective standards to cabin FDA's discretion."

Why does PhRMA want to banish FDA to a "cabin" in the woods as far it's discretion to pre-review DTC ads is concerned?

PhRMA is itching to challenge FDA's authority to regulate DTC advertising in front of the Supreme Court, which is cited several times in PhRMA's comments. For example, PhRMA reminded the FDA (as if that was necessary) that the Supreme Court "recently affirmed that '[s]peech in aid of pharmaceutical marketing .... is a form of expression protected by the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment.' Thus," says PhRMA, "when the FDA restricts the speech of pharmaceutical manufacturers and other regulated entities, the restrictions are subject to scrutiny under the First Amendment."

But the Supreme Court Court is not likely to scrutinize "informal guidance," which is not legally binding. Therefore, PhRMA is pushing the FDA to issue regulations, which carry the weight of law. "Regulations that unduly burden truthful, non-misleading commercial speech about a lawful product," says PhRMA, "hinder consumer choice ... and rarely survive constitutional scrutiny."

Of course, FDA wants to prevent "misleading" drug ads from being aired. Right now, however, it can only cite ads as "misleading" AFTER they have already been aired.

I'm not going to delve into the legal arguments that PhRMA puts forth. You can read them yourself here. I just find it interesting that the drug industry is pushing FDA to stop issuing non-binding guidances in this case as well as in the case of social media (see "WLF & Pfizer Ask Court to Block FDA Guidance on Social Media"). I also like how PhRMA uses "cabin" as a verb, hence the cabin image that accompanies this post.

Hat Tip to @AlecGaffney for alerting me to the publication of PhRMA's comments in the Federal Register, where "occasionally interesting reading [is] to be had."

Friday, May 4, 2012

Obama's Executive Order Spurs Drug Industry to Cooperate with FDA to Ease Drug Shortages

This week marks the six-month anniversary of President Obama signing an Executive Order to help FDA in its efforts to prevent and resolve prescription drug shortages. Following the Executive Order, FDA sent out letters to drug manufacturers asking them to "voluntarily report to FDA if they saw the emerging potential for a drug shortage."

"I am both amazed and delighted to see the progress that’s been made," said FDA Commissioner Margaret Hamburg in a blog post (here). "Early notification to FDA of potential disruptions in drug supply has made a huge difference in our efforts -- and the numbers really tell the story [see chart below]."

"Since reaching out to industry, there has been a six-fold increase in early notifications from manufacturers," said Hamburg. "Also in that six month timeframe, we have been able to prevent 128 drug shortages, and we’re seeing fewer numbers of shortages occur – 42 new drugs in shortage reported in 2012, compared to 90 new shortages at this time last year. This data is a testament to how FDA exercises flexibility and discretion in much of our work on drug shortages and the importance of strong collaboration and constant communication with industry, health professionals, and patients."

According to the above chart, FDA projects that there will be only about 130 actual drug shortages reported in 2012 compared to 250 reported in 2011 and that FDA-industry cooperation will have prevented about 100 additional shortages. By FDA estimates, even if it didn't prevent any shortages, the number of drug shortages in 2012 would be about 230 compared to 250 in 2011. That is, FDA envisions the trend in drug shortages reversing with or without FDA intervention.

But with FDA and industry cooperation, there were only 42 new drugs in shortage reported in 2012, compared to 90 new shortages at this time last year.

"I am both amazed and delighted to see the progress that’s been made," said FDA Commissioner Margaret Hamburg in a blog post (here). "Early notification to FDA of potential disruptions in drug supply has made a huge difference in our efforts -- and the numbers really tell the story [see chart below]."

"Since reaching out to industry, there has been a six-fold increase in early notifications from manufacturers," said Hamburg. "Also in that six month timeframe, we have been able to prevent 128 drug shortages, and we’re seeing fewer numbers of shortages occur – 42 new drugs in shortage reported in 2012, compared to 90 new shortages at this time last year. This data is a testament to how FDA exercises flexibility and discretion in much of our work on drug shortages and the importance of strong collaboration and constant communication with industry, health professionals, and patients."

According to the above chart, FDA projects that there will be only about 130 actual drug shortages reported in 2012 compared to 250 reported in 2011 and that FDA-industry cooperation will have prevented about 100 additional shortages. By FDA estimates, even if it didn't prevent any shortages, the number of drug shortages in 2012 would be about 230 compared to 250 in 2011. That is, FDA envisions the trend in drug shortages reversing with or without FDA intervention.

But with FDA and industry cooperation, there were only 42 new drugs in shortage reported in 2012, compared to 90 new shortages at this time last year.

Thursday, April 26, 2012

Device Makers, e.g. Johnson & Johnson, May Benefit Most from FDA User Fee Bill

"Put simply," says AdvaMed, the trade association of the medical device industry, "the [user fee agreement recently reached between FDA and the medical technology industry] is good for FDA; it is good for industry; and most of all, it is good for American patients."

The House version of the FDA user fee bill, which is currently being marked up, is "widely expected to contain more industry-friendly provisions, especially for medical device makers," according to Politico (here).

Details of "FDA’s ability to reclassify the risk level of devices" may be hidden in the bills. One of these details may concern "a loophole in the law that allows [medical device manufacturers] to submit new products to the FDA for instant review as long as they classify them as an upgrade even if the product has changes that could affect safety," says Consumer Reports. "Companies now use the process 90 percent of the time, according to a report published by Rep. Ed Markey, D-Mass., who is an advocate for industry reform."

Meanwhile, the FDA wants to assign a new bar-code-like identification number to medical devices to help it detect malfunctions in devices AFTER they have been approved. By tapping into medical and billing records from hospitals and insurance companies, FDA hopes to identify faulty devices before they cause deaths, such as the 686 deaths from 2009 to last year connected to automated external defibrillators and at least 20 deaths recently linked to surgically-implanted heart defibrillator wires.

One of the leading manufacturers of heart defibrillation devices is Guidant. A few years ago, it had to recall one of its devices that was linked to several deaths (see NYT article). That derailed a takeover bid by Johnson and Johnson (JNJ). Meanwhile, JNJ is actively growing its medical device business and will soon acquire Synthes -- a Swiss manufacturer of orthopaedic devices -- for $21.3 billion. Devices now account for 40% of JNJ's worldwide sales (see chart below; source of data: CNNMoney.com and Q1 2012 financial statement).

JNJ may position itself as a "consumer" products company, but its main business is pharmaceutical drugs and medical devices. With the acquisition of Synthes, which had sales of nearly $4 billion last year, JNJ's device business will be an even bigger slice of its global sales pie (maybe 43%).

The House version of the FDA user fee bill, which is currently being marked up, is "widely expected to contain more industry-friendly provisions, especially for medical device makers," according to Politico (here).

"One in particular is the HELP bill’s efforts to streamline the FDA’s ability to reclassify the risk level of devices. Whether a device is deemed more, or less, risky can dramatically change the amount of clinical data and other studies required for approval.According to Politico, AdvaMed is still pushing something in between "to preserve some of our due process rights,” AdvaMed's head of government relations (ie, chief lobbyist).